A house divided: When plans for a transitional home in Trenton’s historic district become too close for comfort

Marge Miccio and her husband Robert Wagner took a leap of faith when they purchased their three-bedroom, three-story home on Market Street in Mill Hill for $125 in 1979. The home sale was part of a homestead auction to help revitalize the neighborhood.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, Mill Hill experienced a decline as homeowners fled to the suburbs. According to the Mill Hill Society, vacant properties increased from 3% in 1952 to 17% in 1970. Former Trenton Mayor Arthur Holland was credited for helping to kickstart the revitalization of Mill Hill when he and his wife moved into 138 Mercer Street in 1968. The move was documented by Ebony, The New York Times, Time, and Life magazine.

“But the media saw the significance and symbolism behind the mayor of an aging American city moving in with his poorest and most disgruntled constituents and Art and Betty Holland became worldwide news,” Trentonian columnist LA Parker wrote in the Trentonian’s Capital Century Series.

Over the years, Mill Hill became known as a tight-knit, diverse, and civically engaged community characterized by its distinct 19th-century colorful homes and being just a short walk away from the Trenton Transit Center.

“When we bought our then-abandoned house at 410 Market St. in Mill Hill from a City auction in 1979, we took the big leap because it is located in a historic district that was striving toward restoration and de-converting multi-units to single-family houses,” wrote Miccio in a letter to Trenton City Council in February. After 43 years of building a life in Trenton, which included owning Artifacts Gallery on South Broad Street for 33 years, Miccio and Wagner are ready to put their house up for sale and move closer to family in New Hampshire. The catalyst for their decision was that in February the Greater Mount Zion Community Development Corporation, a non-profit organization based in Trenton, New Jersey had purchased the house next door, with which they share a common wall, and plans to convert the home into a transitional house for formerly incarcerated people. Miccio learned about this when she had a chance encounter with a worker from the nonprofit who was outside the home inspecting the property.

“It took a couple of days for me to absorb the news and then I contacted the council, mayor, and the neighborhood to let them know what was happening,” Miccio said, sitting in her living room surrounded by several pieces of her artwork she has put up for sale in preparation to say goodbye to the capital city for good. “It was like the carpet being pulled up from under you. Our world was being turned upside down and I think my husband and I both had PTSD. We were both in shock,” Miccio described how she felt when she heard about the plans for the house next door.

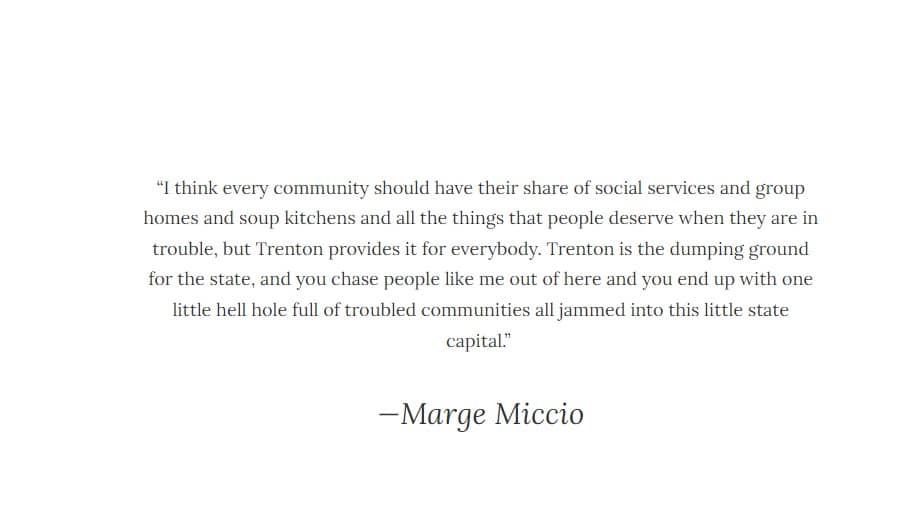

“They didn’t feel the need to tell me anything. Nothing! So why should I talk to them? They are not talking to me,” said Miccio when asked if she ever reached out to the Greater Mount Zion Community Development Corporation to express her concerns about their transitional house. “I think every community should have their share of social services and group homes and soup kitchens and all the things that people deserve when they are in trouble, but Trenton provides it for everybody. Trenton is the dumping ground for the state, and you chase people like me out of here and you end up with one little hell hole full of troubled communities all jammed into this little state capital.”

To underscore her point about Trenton being concentrated in poverty, social services, and non-profits, Miccio sent the Trenton Journal an article published by NJ.com 10 years ago about a woman in Red Bank, New Jersey, fighting homelessness and addiction who was “Given $10 fare and a map to Trenton, because God forbid Red Bank should offer help to their troubled populations when it’s so easy to ship them off to Trenton, NJ’s social services capital,” Miccio exclaimed.

Wagner, who grew up in Trenton, expressed his disappointment with the city allowing a transitional house to operate next door after spending so much time investing in Trenton and working so hard to renovate his home over the years. He describes knowing the details of his house from the plumbing to the electrical work on an “intimate” level. “Your life can change overnight—from noise to the smell of food, the sounds [by who lives next door].”

Miccio said after living in her home for over four decades, both she and her husband knew that they would have to move eventually, but didn’t expect her new neighbors to be the reason why. “We talked about [moving] over the years. So it was in the back of our minds that this house wasn’t going to work for us. My husband is handicapped, the bathroom is upstairs,” she said. Weighing the pros and the cons of making a move, Miccio and Wagner remained in Mill Hill over the years because it was affordable and provided them with a comfortable lifestyle in their retirement years.

As Miccio, 66, and Wagner, 75, look for new housing that can accommodate their lifestyle in New Hampshire, they are blown away by the reality of the affordable housing crisis, “But that’s why you spend your whole life saving,” she resigned.

When Miccio wrote a post on her Facebook page about her ordeal she received support from her Facebook friends with messages such as, “There are plenty of streets in Trenton available for this kind of transitional home like Walnut Ave or Stuyvesant Ave. Why would they put it on one of the prominent, quiet, upkept neighborhoods that people have dedicated their lives investing in? That’s so unfair” and “Why would the city deny a variant for this? It’s all part of the city’s “ghost” master plan, enthusiastically approved by the powers that be in Mercer County government and the surrounding suburbs. Concentration of poverty in Trenton. Drive out home ownership. No limits to the social services/nonprofits. Those who raise concerns are accused of nimbyism [Not In My Back Yard]. Rinse and repeat. Coming soon to a house attached to or next door to yours. Mission accomplished.”

There has been plenty of speculation both online and in person about the purchase of 412 Market Street. “At the last meeting of the Old Mill Hill Society, members expressed concerns about the plans for a transitional home at 412 Market Street. We are working on having direct conversations with the owners,” Oriol Gutierrez, President of the Old Mill Hill Society, revealed. Many questions have remained unanswered, such as the legality of a transitional house moving into a historic district. Was a variance needed to turn this private home into a group facility? While proponents of the transitional house have cited the need for formerly incarcerated men and women to be given the opportunity to rebuild their lives as productive members of society, the intent of opening a transitional home in Mill Hill has many people divided because it underscores such issues as race, class, gentrification, and reformation in the criminal justice system. Many questions have remained unanswered until now. When the Trenton Journal reached out to Rev Dr. Charles Boyer, Interim Director of the Greater Mount Zion Community Development Corporation, the non-profit organization that purchased 412 Market Street, he was more than willing to finally set the record straight.

Addressing a critical need

The Greater Mount Zion Community Development Corporation is dedicated to preserving the history of Mount Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church in Trenton and upholding its legacy by leveraging Greater Mercer County public and private partnerships to create community development, homeownership, and workforce development to solve social problems in Greater Trenton’s historic Black communities. Some of the organization’s current initiatives focuses on Black maternal health, workforce development, historical preservation, and housing.

Reverend Dr. Charles Boyer sits at the helm of the Greater Mount Zion Community Development Corporation and he is the pastor of Greater Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church in Trenton, New Jersey. Boyer is also the Interim Executive Director of a non-partisan Black faith-rooted public policy.

“The church and myself through all of this are being demonized and critiqued,” Boyer said during a recent phone interview. “All critique is fair. We’re big, we’re adults, we can take it, but I think it’s important that folks know that we’re advocates for the marginalized. [Mount Zion AME] is the oldest Black institution in this entire city and the AME church sent me here to do this very kind of work.”

Part of the mission of the African Methodist Episcopal Church Boyer states is to help folks in need, such as men and women coming home from prison. “We’re looking for those in Trenton that have some power and privilege and resources to help us with that work. We’re inviting them to be good neighbors and love their fellow Trentonians regardless of what they’ve been through,” he added.

Boyer told the Trenton Journal that the transitional house is expected to open in the spring and will house about three to four people at a time for six months to a year—none of them who are listed on a sex offenders registry—and are Trentonians who have lived in Trenton prior to incarceration. Some of the men he has identified to move into the house are already couch surfing or desperately seeking housing in the city and are over the age of 40. According to the New Jersey Department of Corrections, 27% of all incarcerated persons are 30 years of age or younger and Boyer echoes that statistic,“The recidivism rate is extraordinarily low for people over the age of 40 because crime is a young person’s game,” Boyer stated. In the future, the transitional house may shelter different populations such as young people who have aged out of the foster care system or people who are seeking refuge from a domestic violence relationship.

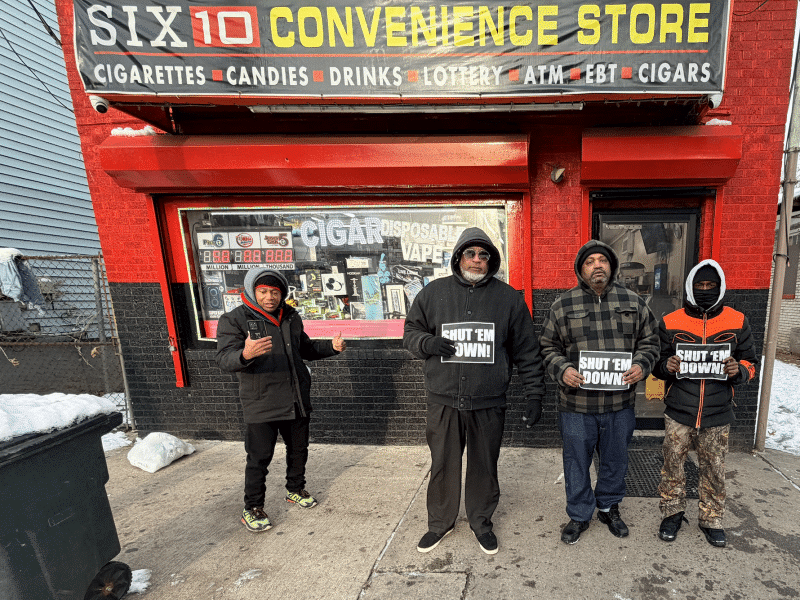

The impending transitional house, which Boyer makes a clear distinction is not a halfway house, but housing he refers to as “communal living,” will be staffed and supervised by members of the Salvation and Social Justice Street Team to make sure everything is kept in order at all times. The transitional house also plans to have wrap-around services which include food, employment, and mental health resources. “You know housing is not an easy thing when you’ve been formerly incarcerated even though we have a law in place that is supposed to protect formerly incarcerated people from housing discrimination,” Boyer affirmed, later adding the importance of opening up housing for this population.

“There is no one-size-fits-all model for reentry,” said Assistant Commissioner of the Division of Programs for the Department of Corrections, Dr. Darcella Sessomes, in a 2021 press release announcing a $3 million grant to expand support of reentry services for individuals exiting the state’s correctional system.

Some of the backlash the Greater Mount Zion Community Development Corporation has faced stems from the lack of communication the nonprofit has had with residents in Mill Hill. Boyer admits that things could have been handled in a better way to give the residents more detail about the transitional house. However, he said he’s still open to meeting with key members of the community to answer questions and address their concerns.

According to Kevin McHugh, Executive Director of the Reentry Coalition of New Jersey, transitional houses moving into residential neighborhoods amid controversy is standard modus operandi. McHugh says that part of his organization’s mission is to educate the public on reentry. “I understand the community’s concerns even though I worked for the state at the time [when] I opened [transitional homes]. It immediately becomes a political issue. In fact, I was kind of like a ghost in a way, because the state never wanted to announce its intention.” McHugh recalls going to public hearings and zone board meetings to rally community support when he spent time opening up transitional homes and halfway houses in New Jersey. “The approach that you really need to take is to get to know your neighbors and understand what the neighborhood is like. The right way to do it is to have coffee klatches, sit down with people, and let them know what your intentions are and what you need to do.”

Second Chances

Rhonda Lige knows firsthand the impact that living in a transitional home can have on someone coming out of prison trying to get back on their feet. Lige spent seven years incarcerated at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for theft by deception charges. Lige has lived in several transitional homes since she was released from prison and says there are several barriers that people coming out of prison have to face, which include finding stable housing.

“Once the neighbors found out who we were even though we weren’t rowdy—we came and we went to work and we went to school and that was it. [The neighbors] still had this big uproar…taking pictures of us leaving and coming back. They were really trying to build a case to get this house shut down because it was a house of formerly incarcerated women.”

In hindsight, Lige admits the concept of opening a transitional house in a residential neighborhood in the early 2000s on Adeline Avenue in Trenton might have been too new for some residents to understand. The New Brunswick resident said living in transitional housing after her release from prison allowed her to pursue her bachelor’s degree at Rutgers University and she is now studying for her doctorate. “It’s a whole bunch of [rejections] especially with the stigma of having a record. If you have a background of any sort, it’s a barrier,” Lige said. “Just because I’ve been in prison it doesn’t [mean I can’t be reformed].”

On March 19, 2024, during a city council meeting, North Ward Councilwoman Jennifer Williams, who represents the district where the transitional house will be held, expressed her hope that the Mill Hill community and the Greater Mount Zion Community Development Corporation and its occupants can come together to have a mutual understanding. “We need to recreate the expectation that we are going to have a conversation and not have people fly off the handle on the Internet because that does nothing positive,” she later added, “These conversations are going to happen and that’s important, because we’re in a vacuum otherwise and that’s not the way to raise up the city and bring the city forward.”