After Beakes Street assault, Trenton grapples with violence, vices, and who owns the block

Last week, when West Ward residents learned that a local Six 10 Convenience store employee allegedly bludgeoned a resident he believed was stealing, it sparked fresh debate over a familiar problem: The fragile relationship between non-black shopkeepers and their largely black clientele in some Trenton neighborhoods.

A video shared on Facebook December 8th by El Roy Clark highlighted the worst case: In it a man stands outside the Beakes Street shop with a bloodied face, appearing dazed as he nods to confirm Clark’s assertion that “this Indian dude busted my man in the head with a bat. . . .” While still videotaping, Clark prompts “somebody needs to come do something about this.”

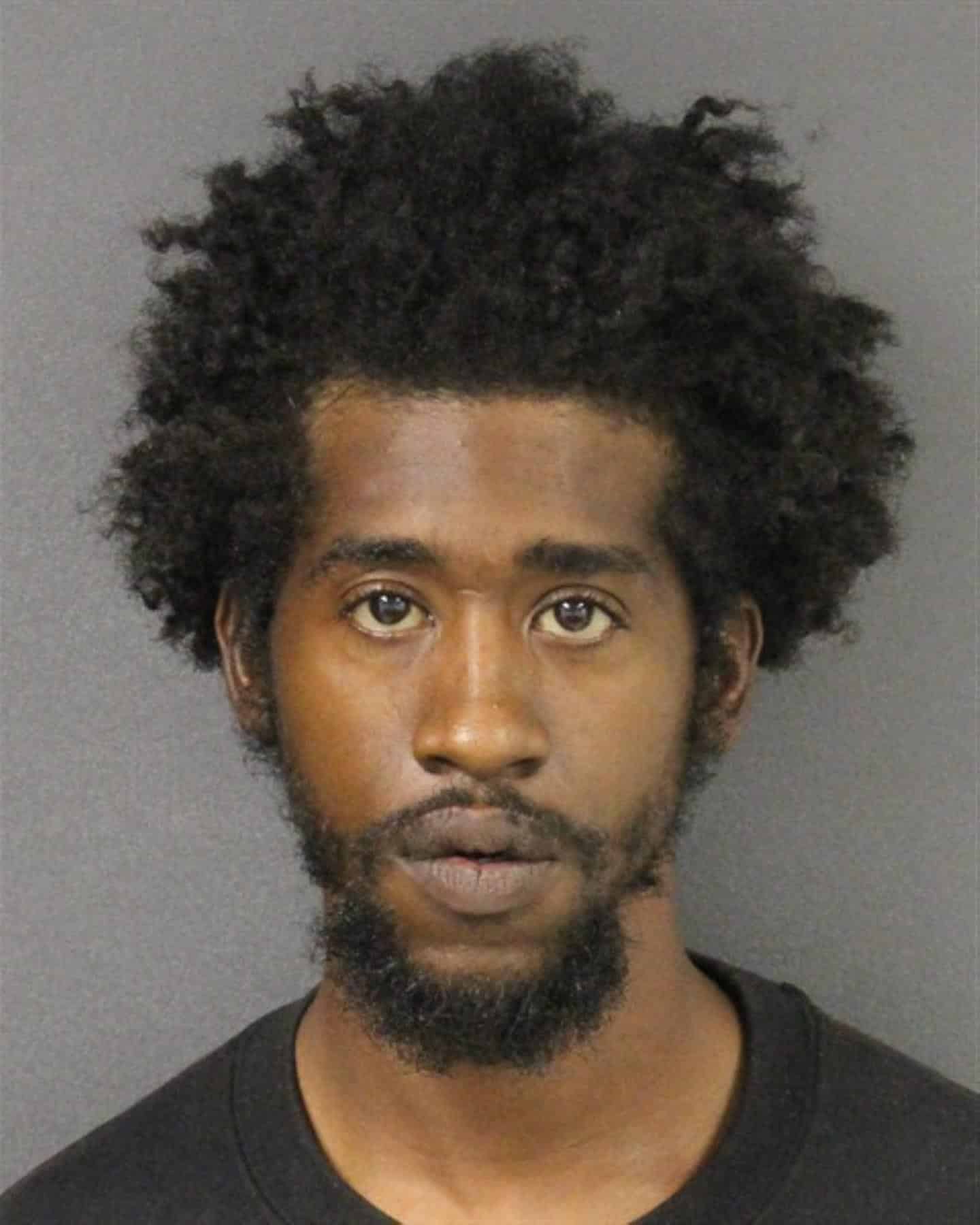

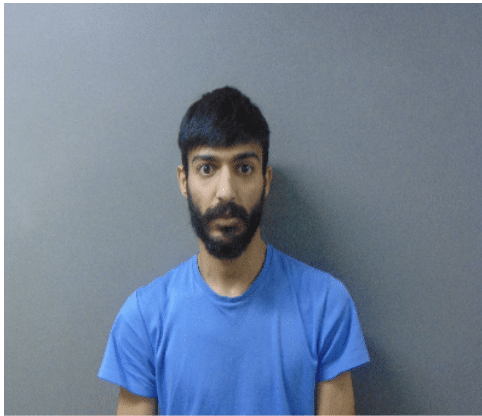

The next day, Trenton police arrested 26-year-old Six 10 employee Animol Sethi for aggravated assault. By December 17th, the shopowner, who identified himself only as Ricky, said he had fired Sethi; and the victim, a man known locally as Kenny, had been treated and released from Capitol Health Regional Medical Center for non-life-threatening injuries. (At press time, he could not be reached for comment.)

Mayor Reed Gusciora told the Trenton Journal that, “Any incident involving violence in our community is taken seriously” and that “we encourage residents and business owners alike to rely on lawful conflict resolution.”

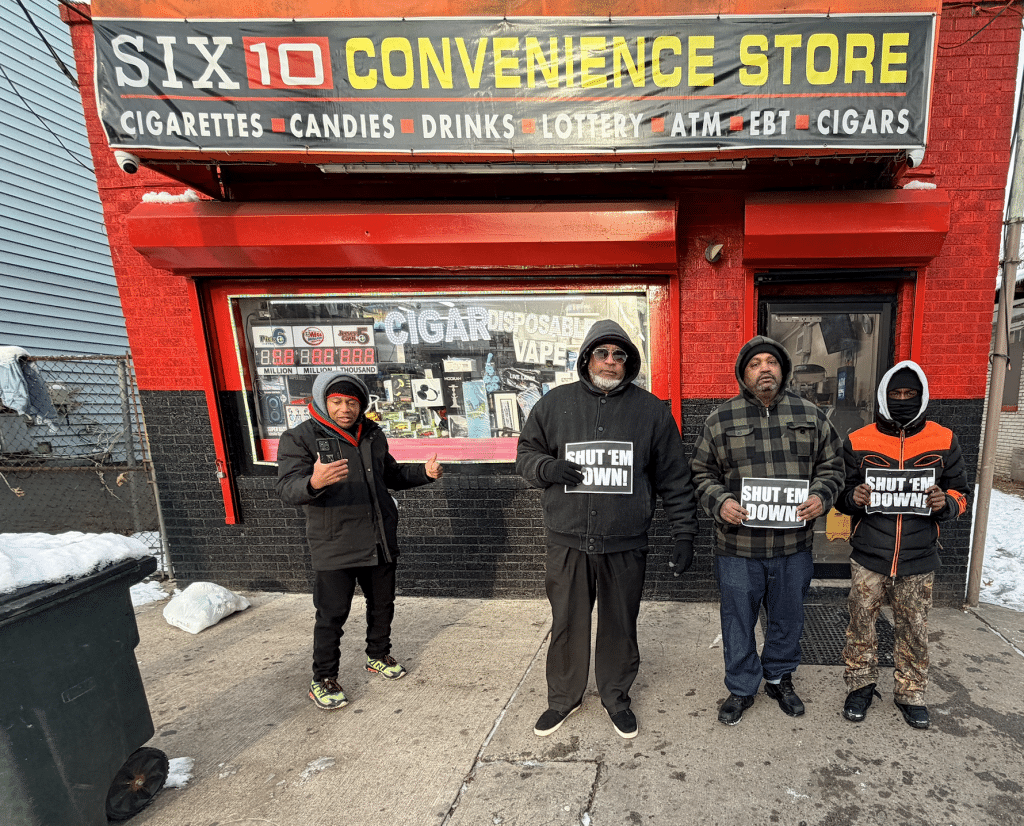

Community activist, founder of Mind Body Activism, and a former candidate for the North Ward council seat, Divine Allah, has issued a different call-to-action: “Our goal is to shut [the store] down.” He and a handful of others have staged a sidewalk protest outside the shop for the past two weeks.

“I don’t know why they are protesting,” said the owner of Six 10, “because the law has already punished the man and I fired him.”

Protestors, however, view the assault as a symptom of bigger ongoing harms that businesses like Six 10 seem to perpetuate in Black communities. “Look at what they sell,” Divine Allah says, “vapes, lottery tickets, cigarettes.”

Meanwhile, the closest conventional grocery stores, such as ShopRite and Aldi, are in Ewing, at least two miles away. “Fairly close, but then you get into the issue of transportation,” he says, referring to the logistical challenge faced by residents who are elderly or have small children in tow. Conversely, Six 10, across the street or down the block, is “real convenient,” he says, adding “They’re popping up all over the city.”

At 16 Beakes Street specifically, Six 10’s owner is the latest of five who Divine Allah has observed come and go over the last 25 years. He categorizes them as “side-street bodegas,” which may carry milk or deli meat, but mostly push vapes and cigarettes. “You may see three rolls of toilet paper, but eight shelves of every type of cigarette. Unfortunately, they’re not stocking the stuff a person really needs to sustain a family.”

Other community leaders share Divine Allah’s concerns, but disagree that closing one location will make much of a difference (Six 10 has several in Trenton, including one adjacent to City Hall).

“If you just keep running people out, it’s going to be a revolving door,” says Lakisha Adams, director of the Trenton Center for Healing Unity and Belonging (HUB).

Instead, her organization supports community members in finding common ground and trying to understand each other. “What do you identify as the root cause here? What are potential ways we can address the root cause, so that whoever is operating that business has a better understanding of the community? If the shopkeeper is losing money, he may be in a position where he’s willing to have that dialogue.”

The center, which opened a year ago as one of four New Jersey HUBs providing young people with a less-punitive alternative to the juvenile justice system, has also begun conducting two–day, community-building training sessions with Trenton police officers. “This,” says Adams, “is the very same thing that needs to happen [for shopkeepers and some West Ward residents].”

In its first year, the HUB has trained 150 people in the steps of its hallmark process called “the restorative circle.”

Ideally, this involves bringing together everyone involved in a harm situation to help them discuss the harm; figure out a solution or resolution, and establish an agreement on how to move forward. A high priority is placed on having participants accept accountability for harm they’ve caused, because this is what increases the likelihood that it won’t happen again, Adams explains. “So, do we want punishment? Or do we want the increased likelihood that this won’t happen again?”

Still, few can deny a seeming pattern of outsider owners inexplicably eager to invest in commercial property in areas steeped in problems: The same block of Beakes Street that holds Six 10 was this June the site of a hit-and-run that severed a pedestrian’s leg; the scene of a deadly New Year’s Eve shooting closing out 2021; witness to the deadly shooting of a teen in 2013; and the site of a stabbing in 2015.

What type of outsider business owner sees themselves as a fit? DivineAllah has a theory: “Unfortunately, we get locked into only wanting to support something that feeds the vices that people may have. That’s basically the science of it.”

Kelly Beamon is a lifelong journalist who started her career at The Trenton Times and later moved through significant roles at Dow Jones, Time Inc., McGraw Hill, and Nielsen. Her work has appeared in Essence and Black Enterprise magazines as well as This Old House, Architectural Record, Interior Design, and The Architect’s Newspaper.