A Utility Under Pressure: Compliance Failures, Rate Hikes, and Lingering Public Distrust

Drinking water around the globe is drying up faster than it can naturally be replenished. Water insecurity is the most critical issue facing communities worldwide, including Trenton, with projected demands far outpacing supply by 2030. Considering the threat of a global water crisis, there is a significant incentive for the City of Trenton, neighboring townships, and the state to reach an equitable solution for providing safe and reliable water access for ratepayers and taxpayers alike.

There is, nevertheless, increasing controversy around the ability of Trenton Water Works (TWW) to provide all its customers – both taxpayers from the city of Trenton and ratepayers from surrounding townships – with safe and reliable access to drinking water. Many organizations in Mercer County, including the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), fear that, save for some fundamental re-organization of the utility, systemic failure is all but guaranteed, stranding 200,000 customers without water.

In turn, the NJDEP, as well as leadership from Hamilton, Ewing, Hopewell, and Lawrence, are pressing Trenton leadership to adopt regionalization of TWW to resolve customers’ water woes.

In an August 2025 letter to the Trenton City Council, NJDEP commissioner Shawn LaTourette says, “The facts demonstrate that TWW is at extremely high risk of systemic failure, and that the City does not possess the requisite technical, managerial, and financial capacity to properly address these risks and ensure TWW’s long-term operational continuity.”

Later that month, a special city council session with LaTourette on regionalization yielded no conclusion on a path forward for TWW. Even less so, it yielded a clear definition of what regionalization is.

In principle, regionalization would allow for the creation of a quasi-government entity led by a board with representatives from serviced areas. That means the utility would no longer be under the governance of Trenton’s Department of Water and Sewer, and that the regionalized board would be able to move and make decisions quickly. The entity would not be constrained by Trenton’s government’s requirement for special agreements or tense political relationships, yet would remain under Trenton ownership.

In principle, regionalization would fast-track improvements critical to not only stabilizing but also enhancing operations at the water utility. In actuality, however, some Trenton residents and city leadership are challenging the sincerity of this recent push for regionalization.

Trenton’s valuable asset

“[New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) commissioner Shawn LaTourette] said Trenton Water Works must be untied from the city government because no one wants to work with Trenton, yet he’s proposing to tie it to the city government of for richer, whiter towns?” Trenton resident, Caroline Clarke, told the Trenton Journal. “So, the issue isn’t the Trenton Water Works. It’s not about safety. It’s about a predominantly Black city – Trenton – owning an asset that is very valuable, so valuable that the two Wall Street governors [Phil Murphy and John Corzine] are hell bent on selling it to Wall Street.”

“This is what it looks like to create hoods,” Clarke continued. “They take out all the resources – Trenton Water Works is the last [major] source of revenue for Trenton – and then they abandon us. All these groups [major media outlets] are writing about how aggressive we are, but we’re [just] defending ours.”

Across more than 300 pages of independent reporting conducted on behalf of NJDEP, it was found that TWW facilities are operating with compromised infrastructure and overworked employees.

Ensuring that customers won’t have to worry about their water will require improving TWW’s management capacity and expertise, removing lead pipes, replacing water mains and meters, replacing the open-air Pennington Avenue reservoir with a decentralized storage tank system, and clearing debt. Altogether, that will cost $230,000,000 over five years. This number balloons to $575,000,000 if one considers the entire timeline for capital improvements between 2024-2033.

How, then, might Trentonians expect to fund capital improvements and reduce debt if not through regionalization?

One solution is to increase rates for TWW customers.

Recently, TWW leadership, in collaboration with municipal consultant Raftelis, identified rate hikes that would pay for capital improvements through 2030 but that they believed wouldn’t hamstring customers.

These proposed rate hikes would occur between 2026 and 2030. Altogether, customers could expect a 60% increase in their annual bill. Currently, TWW is the seventh cheapest water utility in the state. The proposed rate hike would make TWW the fourth most expensive water utility in the state — albeit under current statewide public and private water utility rates. This may not be a problem for families in higher-income municipalities such as Hamilton township, where median household incomes are as high as $100,000, according to the US Census Bureau data. However, as many as 1-in-5 people in Trenton live below the poverty line, and the median household income currently sits below $50,000.

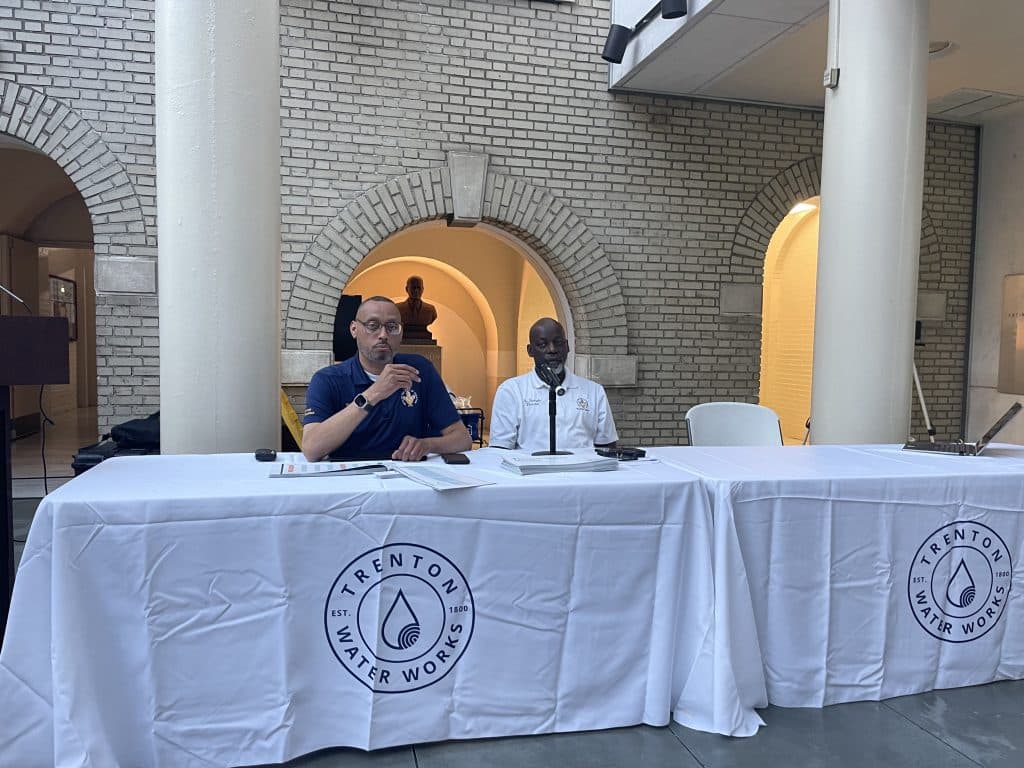

At an open session at Trenton City Hall on August 25th, TWW and Raftelis aimed to assuage customer concerns about the proposed rate hikes. Meeting attendees, however, struggled to swallow the reasoning behind these hikes.

First, attendees were unsure if the capital improvements would be finished in time with the rate hikes, if at all. “I’ve been living in Trenton for 20 years. For at least 15 of those years, there’s been talk of decommissioning the Pennington reservoir. How is this all going to be done in a timely manner? What happens if these projects aren’t completed in the next five years?” one attendee asked.

Second, attendees were unsure if the rate hikes would benefit current employees of the water utility. “All City of Trenton residents know where this is headed…I’m frustrated by these increases. People are living paycheck-to-paycheck,” one attendee said. “You’re saying you need all these [capital improvements]…Will these hikes improve wages for employees, who people were saying already [are] overworked and underpaid?”

Finally, attendees lacked clarity on how money is being spent currently by both TWW and the City of Trenton to justify the rate hikes. “Unfortunately, municipal finances are complicated,” Michael Walker, TWW chief of communications and senior customer care officer, told attendees. Notably, the financial director was not at the meeting.

“This is not a financial issue”, argued Trenton Orbit co-founder, Michael Ranallo, in response to Mr. Walker’s point on finances. “It’s a trust issue.”

Some Trenton residents do not trust local authorities to make decisions that will prioritize benefits for taxpayers over ratepayers in the nearby townships or to raise their bottom line.

“The timing of these rate hikes is suspicious,” Clarke told the Trenton Journal after the rate hikes meeting. “The DEP push for regionalization [and the rate hikes together] are readying us for sale.”

Residents are adamant that the proposed rate hikes, in tandem with the push for regionalization, are part of a calculated effort to sell off the water utility to New Jersey American Water.

Compared to water utilities statewide, which commonly increase their rates by as much as 5% every year to keep up with operations and inflation, rate hikes for TWW are rare. The Trenton City Council last voted to increase the cost of water in 2020. Before that, the most recent hike was in 2008. Former head of TWW Brent Cacallori said to NJ.com in 2014 that the 2005-2008 rate hikes, “were implemented so customers wouldn’t be shocked by the rates that American Water would charge them once it took over.”

The city failed to sell the utility between 2008 and 2010 after residents voted against the sale. As a result of this referendum, and so long as the utility is under governance by the city, any future push to sell TWW will first require a vote by Trenton residents.

“They [the state] want [TWW] to regionalize so that they can work around the referendum,” Clarke said. “They’ve been trying to regionalize [since] Murphy [entered office].”

Decades of compliance issues and aging infrastructure

In fact, in June 2018, the 218th State Legislature of New Jersey introduced a bill sponsored by Assemblymen Wayne P. DeAngelo and Dan Benson (District 14) that called for regionalizing TWW. The bill cites numerous violations of noncompliance documented by the NJDEP as one reason for the need to regionalize.

“They’re documenting [noncompliance by] TWW to take it over,” Clarke continued. Since 2018, TWW has been documented by the DEP for 16 instances of noncompliance. “That’s up from two citations for noncompliance between 2009-2018…They’re trying to set us [the city] up and get council to turn it over to the DEP.”

At what point in the push for regionalization did TWW begin its search for a rate hike? Mr. Walker answered, “During.”

But do Trenton residents believe in the quality of water provided by TWW? It’s complicated.

“My water is not good…I’m on a fixed income, and I just got caught up on my water bill [after being behind for months]. I can’t afford the rate hikes, and I don’t feel comfortable [with the idea of] paying [more] when my water is brown and the pressure is [frequently] low,” said one resident who asked not to be identified.

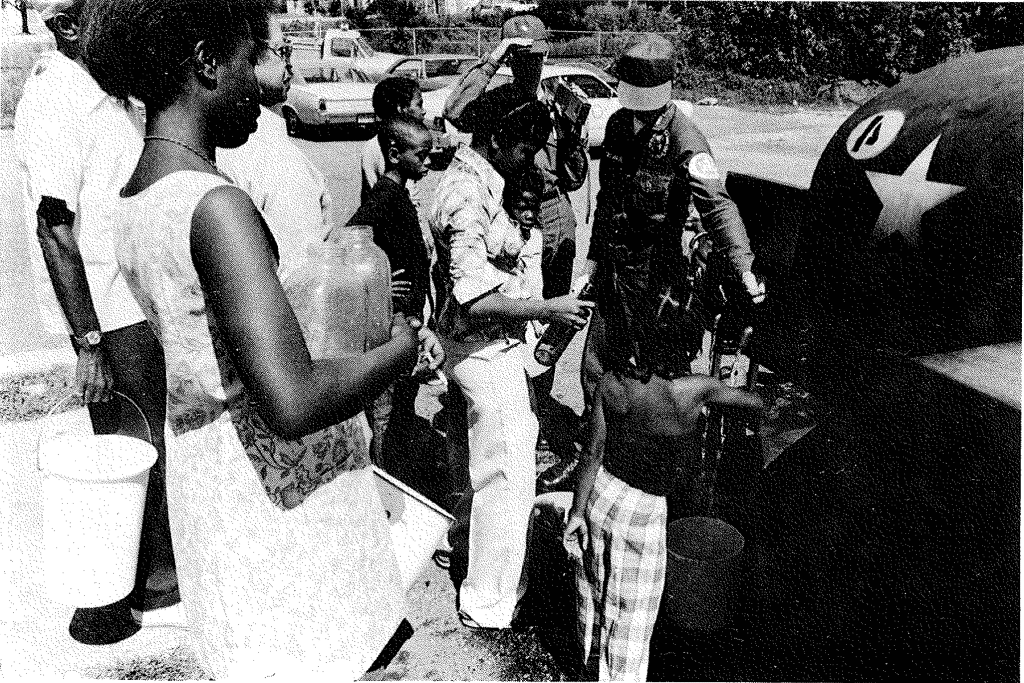

Older pipes are among the leading – though not only – causes of brown water running from the faucet. Many of TWW’s service regions contain older lead pipes, which can be problematic beyond discolored water: lead exposure has remained an environmental justice issue for many Trenton residents because of the lifelong neurological injuries caused by lead poisoning, especially from an early age.

TWW is working to replace lead piping, but struggles to get residents to sign up for the replacement program. “Getting people to sign up to remove lead service lines in Trenton is a significant and costly challenge – anywhere from $7,000 – $12,000 per home. And this is a problem across all four townships, not just Trenton. [It’s] just one complicated problem we have to figure out,” said Walker.

Legionnaire’s disease, which is caused by a strain of bacteria that thrives in warm environments and stagnant water in old infrastructure, has also afflicted Trenton at a higher rate than any other municipality in New Jersey. Low-income communities like Trenton, troubled by declining infrastructure, are disproportionately impacted by Legionnaires’ disease. Longer summers caused by global warming portend more Legionnaire’s disease outbreaks in the future. Cooling low-income communities that disproportionately live on urban heat islands will become, paradoxically, more challenging on a hotter planet.

Short-term political ambitions, as well as decades of unsatisfactory management of TWW, are encumbering the collective ability to envision a long-term solution to delivering clean water to people. Short of a comprehensive solution for the utility, water troubles that have plagued the heart of New Jersey for generations will be dwarfed by suffering caused by the global water crisis looming in the not-so-distant future.