Planting seeds for the next generation of Trentonians

The intersection of East State Street and Johnston Avenue is a tale of two streets: north of Johnston Ave, trees with leaves amber, orange, and brown swallow up East State Street; heading south sparse trees are sprinkled along the sidewalk.

Just around the corner from this intersection Jay Watson, Co-Executive Director of the New Jersey Conservation Foundation, is leading work to grow the number of trees along East State Street and throughout the city.

The NJ Conservation Foundation and its partners, including the City of Trenton, Isles, and the Outdoor Equity Alliance among others, were awarded over $1.3 million dollars to plant over 1,000 trees throughout Trenton. Building a “green corridor” along East State Street is a focal point of this project. The aim of this green corridor is to connect current and future green spaces in Trenton including Cadwalader Park and planned forests plazas on North Clinton.

However, Watson is quick to admit that simply planting trees is not enough.

“A big part of our project is making sure that we’re taking care of existing trees [and] that they’re receiving adequate maintenance.”

Though they may not look it as their branches become bare, but the trees that line our streets are important for reducing floods and noise and keeping temperatures cool across the city. Temperatures in neighborhoods without trees can be as high as 13oF warmer than neighborhoods with trees; what’s known as the “Urban Heat Island effect”. Last summer was the hottest ever recorded by NASA; the summer of 2022 was the third summer hottest recorded in New Jersey.

“I wish that I was a bolder photographer,” Watson confesses, “I mean you could see people were congregating underneath trees when it was 95oF outside. Probably like a half dozen people. And kids at Sprouts Academy, when they go outside, they sit under that one tree,” he says pointing at a PowerPoint picture, “and it isn’t even on the school’s property. The kids had to leave school to find shade!”

“But many of those people [sitting under the trees] aren’t looking at the tree as providing a valuable service. Somewhere along the way that connection [between people and nature] was broken.”

Today, most predominantly Black, low-income communities are without trees because of their legacy as formerly “redlined” communities – communities designated by the Federal Housing Authority to be “hazardous” zones – that were divested from during the New Deal era, notably characterized as a time of aggressive federal aid. Formerly redlined neighborhoods have gone so long living without all things green that the notion of streets densely packed with trees has become a foreign concept to many.

The biggest obstacle Watson and others are working through now is the aversion residents have towards trees. “I was talking to a couple of women at the River Days event [in September] and they told me they didn’t want trees hanging over their homes. They’re concerned about the rodents and bugs that might get into their homes.” Indeed, many residents don’t want trees in Trenton because of the harms they can cause.

“Our current goal is to make sure that people are on board. Planting a 1,000 trees won’t mean a thing if the people don’t see it as a positive thing,” Watson says. To remedy this, NJ Conservation Foundation and the Outdoor Equity Alliance are working with high school students and residents to engage the community on the benefits of trees.

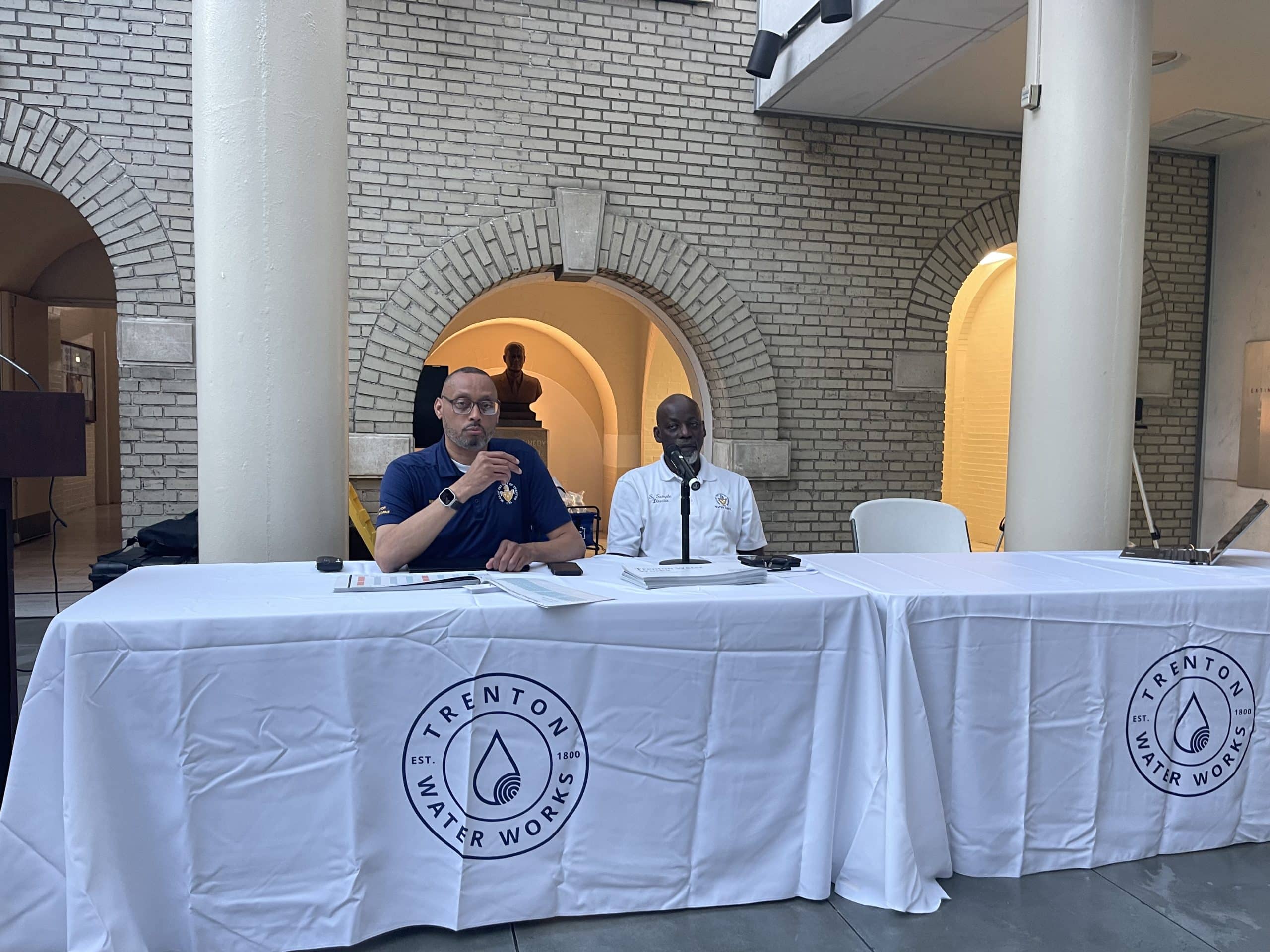

“One brother from Trenton Water Works called me and he said, ‘Listen Mr. Watson, I appreciate what you’re doing, but I don’t want any tree out in front of my home. I’m in the ground all the time fixing water line breaks caused by trees’ roots. I don’t need that problem.’ But those trees were looking for water that was already in the ground, so the tree didn’t really cause the problem. It was an indicator of an already existing problem.”

Watson hopes that by empowering young people to lead the community they can help people see how the benefits of green streets outweighs any of the negatives, especially when you consider that many of these trees will take time to grow. “Most of the trees that people are concerned with [take 50-75 years to grow to maturity] and [have thus far not] received the maintenance they need. So, by the time we plant [1,000 trees] those people will have moved out or moved on.”

“For me, I want to end my career planting trees in Trenton,” Watson confesses. “There’s an old saying [out of India by Rabindranath Tagore] about planting trees that expresses my motivation right now: ‘The one who plants trees, knowing they will never sit in their shade, has at least started to understand the meaning of life.’”

And for the young tree ambassadors, Watson hopes to cultivate in them the tools to become better stewards in the future. “Trenton’s trees are going to need to be taken care of if we expect them to continue to take care of us.”

Harrison Watson is a PhD student at Princeton University and has written environmentally-focused stories with various outlets including These Times and Next City.