Preserving the legacy of African American Revolutionary Soldiers

You can hardly be in Trenton more than a day and not know the importance of the battle here that helped turn the tide of the American Revolution. What is less widely known is the role of African-Americans in the Revolution.

Leon Brooks, originally from Philadelphia, arrived here in 1987 to work as a database coordinator for the library at Trenton State College. Through the years, he worked in several info tech jobs, eventually retiring from a position with the State of New Jersey in 2014. Along the way he stepped in to run the library at Trenton Central High School, where he really began to bring life to his long-time interest in history.

In 2001, Mr. Brooks first explored the world of military reenactments when he was invited to join re-enactors of the Sixth Regiment United States Colored Troops of the Union Army in the Civil War, which in the 1860s was based at Camp William Penn in Chalfont, Pennsylvania. Brooks recalls his first adventure as a newbie with the Sixth Regiment: “I didn’t have any experience so they threw me in a uniform and made me a patient in the field hospital. It’s the only way to learn history!” He seized the opportunity to create a living history program at Trenton High.

Richard Patterson, then Executive Director of the Old Barracks Museum downtown, introduced Leon to the role of Blacks in the American Revolution. “It’s odd that I had never really learned much about this piece of the story, even though I studied history at Cheyney State, an HBCU. I had never really imagined what Blacks did during the Revolution. The Continental Army and militias included 3,000 to 5,000 Black soldiers but the British recruited more, about 12,000.”

As Nikole Hannah-Jones recounts in The 1619 Project, the Declaration of Independence cites tension over slavery as one of the grievances against Great Britain: “He [the King] has excited domestic insurrections amongst us . . . ,” referring to slave uprisings that were in some cases encouraged by the British. When George Washington was leading the early phase of the Revolution in Massachusetts, he excluded Blacks from service, but the British took advantage of their quest for emancipation and offered immediate freedom to any who would serve. As a side note, England abolished slavery decades ahead of the United States. At the end of the war, England evacuated many of its Black allied troops to England or to Nova Scotia and other parts of Canada; several hundred ended up in Sierra Leone under British protection.

Leon first began soldiering in the “Rev War” as he calls it, as a member of the First Rhode Island Regiment, which was about 80% Black and 20% Native American; the only Whites were the officers. They wore cream-colored uniforms that were the hand-me-downs from the French allies; this regiment has currently been involved in events hosted by the William Trent House, where the First Rhode Island was stationed for parts of the war.

And here comes the “By Sea” part: Hanging out with the New England guys, Leon connected with yet another unit, the Marblehead Marines. Marblehead, a few miles north of Boston, was the home of General John Glover, a fisherman and seafarer who organized one of the first units of the United States Marines. The Marblehead Marines were the boatmen who rowed Washington across the Delaware. Without Marblehead, there is no Washington’s Crossing. Having had some exposure to life at sea from his time in the Naval Reserve, Leon was drawn to yet another reenactor unit. He has participated in the Battles of Trenton, Red Bank, and many others; some have been conventional eighteenth-century battles, but he describes Trenton and Germantown as “street fights.” Despite Washington’s view of the “indignity” of enlisting Blacks, the Marbleheaders included a number of African-Americans.

So now we move from military reenactments to maritime history and ecology. Seeking to learn more about the world of sailing ships, Leon signed on as a volunteer with the Philadelphia Ship Preservation Guild, which maintains the Gazela Primeiro. The Gazela is a three-masted ship that once served the Portuguese fishing trade on the Grand Banks, and is now at home at Penn’s Landing in Philadelphia as an educational/tourist attraction.

Leon is immersed in the social history of seafarers, with special attention to the Black crew members. Whether on a merchant, naval, or pirate vessel, seafaring has always been one of the world’s most dangerous lines of work. Merchant ships on “the highway of the world” always had a need for manpower, and it was never easy to recruit crew members. Black sailors, both free and enslaved, were not at all uncommon; in some instances enslaved people were sold to captains, who would of course reap the fruit of their stolen labor. “Captains wouldn’t look too closely to see whether Black men were free or escaped, because they needed all the help they could get. Life aboard ship encourages people to be self-reliant and develop leadership skills, so a number of the prominent people in Black history came from a maritime background — think of Crispus Attucks, who was killed in the Boston Massacre. Then there’s Robert Smalls. . . .” Smalls was a harbor pilot in South Carolina who freed himself and his family by stealing a Confederate ship in 1862. He went on to become a US Congressman before Jim Crow took hold in the South.

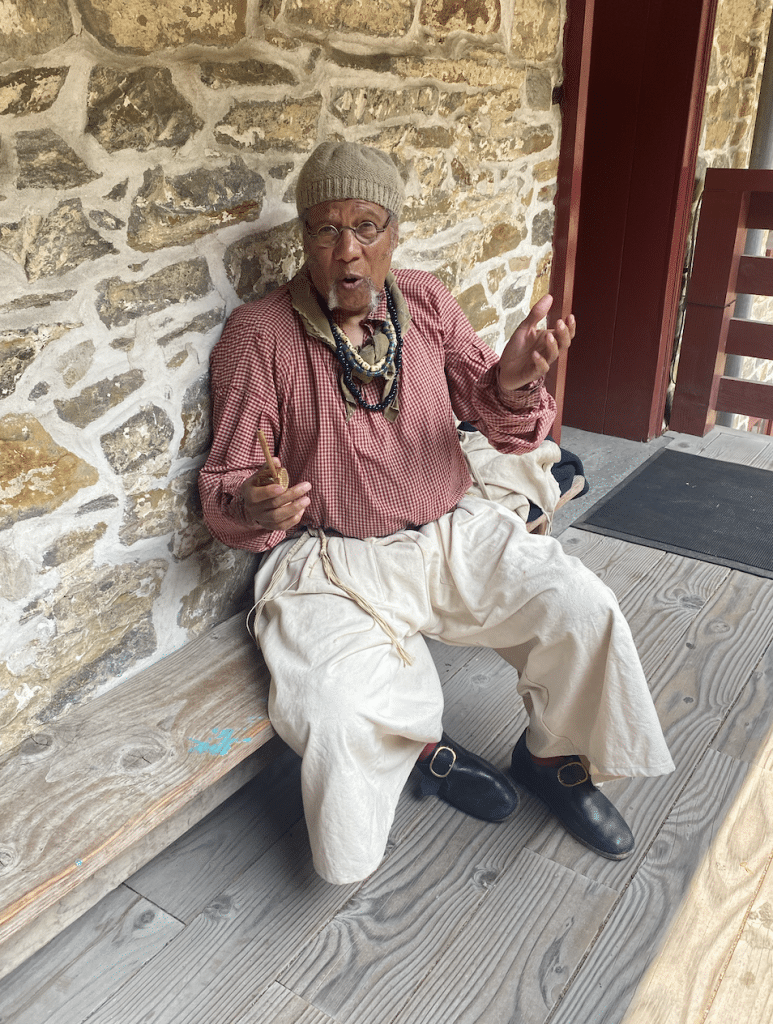

When we met, Leon was attired in the “kit” of a seafarer, and he brought along his blue jacket typical of a Marblehead Marine. He wears “slops” over his optional breeches, and when he does dirty work on the Gazela or the Meerwald he’s fine with getting tar on them for the sake of authenticity. With his tattered gingham shirt he wears “trade beads” and sometimes earrings: “These were what we’d use for currency in foreign ports — in South America, the Mediterranean, wherever.” He wears Ben Franklin-style bifocals that clearly show the line across the middle.

In 2015, a Gazela crewmate invited Leon to join the crew of the Meerwald, an oystering schooner based in Bivalve (yes, that’s a real place) in South Jersey. “At the time I was interested in the work of a ship’s carpenter, so I got to learn about that kind of labor and I lived in the crewhouse there.” Built in 1922, the Meerwald harvested the once abundant oysters on Delaware Bay, and briefly served as a firefighting ship during World War II (it has an auxiliary diesel motor in addition to sails). Leon serves as a deckhand and educator on the Meerwald. He enthusiastically welcomes school groups on board to learn the history of the ship and of oystering, with an organized component on environmental concerns, such as water chemistry and the health of the Delaware Watershed.

Earlier in the twentieth century there were dozens of oyster boats on the Delaware Bay, harvesting and shipping trainloads worth of oysters to Philadelphia and beyond. The crop has been devastated over the years by occasional parasitic or viral outbreaks, some sparked by pollution. Waters warmed by climate change are a continuing threat. Oysters are not only a great source of protein; they also do an important job by filtering water. The health of the oceans around the world is in severe danger, and estuaries like the Delaware and Chesapeake have a critical role in efforts to restore environmental stability.

This article originally appeared in the Trenton Journal Social Justice print magazine, click here for more information.