Revitalizing Trenton: Navigating the Challenges and Opportunities of Brownfields Redevelopment

This holiday season, Trenton Area Soup Kitchen (TASK) will provide hundreds of families across the city with warm meals topped with wholesome veggies supplied by Capital City Farm, but before Capital City Farm was feeding families nutritous foods it was designated as a toxic location known as a brownfield.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, a brownfield is “a property, the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant.”

For a long time, Capital City Farm was a rail spur that ran underneath North Clinton Avenue. And for some time after, it was a dumping site for demolition debris. The site was littered with 45s and used tires and harmful chemicals like lead.

The site almost wasn’t a farm. “[13 years ago] it was set to be a junkyard,” said Jay Watson of the New Jersey Conservation Foundation. “But [the D&R Greenway Land Trust] purchased the property to turn it into an urban agricultural and education center.” First, however, it needed to be cleaned.

The site was cleaned using what’s called a “cap-and-fill” remediation process. This means that gravel was first placed over contaminated soil – to “cap” the contaminants – then fresh topsoil was placed over that gravel. The site was cleaned between 2015 and 2016. The first growing season for Capital City Farm took place in 2016. “With the produce from Capital City Farm TASK was able to set up a salad bar,” said Watson.

The project received much help from brownfield experts that have worked in Trenton for decades. Leah Yasenchak, co-owner of Brownfield Redevelopment Solutions (BRS) Inc. and former employee of the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Air and Radiation, is one of those experts. Yasenchak was among the first people in Trenton working on brownfields in 1995. That year the EPA began their brownfield redevelopment granting program. Grantees received $200,000 and assistance from an EPA employee for hazardous waste site assessments – investigations to figure out what chemicals are the soils of sites selected for redevelopment.

Yasenchak’s company, BRS Inc, now works across America helping manage brownfield redevelopment projects. “Trenton is one of the best in the nation at brownfield redevelopment work,” Yasenchak asserted. Because, “Trenton has James.”

James, or J.R. Capasso, is the brownfield coordinator for Trenton. “I’ve been in the work almost 22 years,” Capasso said. “I was an environmental consultant before seeing an ad [for the brownfields coordinator] in the newspaper.”

Before Capasso took the position, Michele Christina was the brownfield coordinator for the city. Christina is the co-owner of BRS Inc with Yasenchak.

“When I was consultant, [the idea of] brownfields was sort of taking off. Back then they were referred to as hazardous waste sites. [The term] brownfields came along more like in the mid-1990s. The city was taking ownership of property and they learned that it was not easy to turn around and develop it and sell it.”

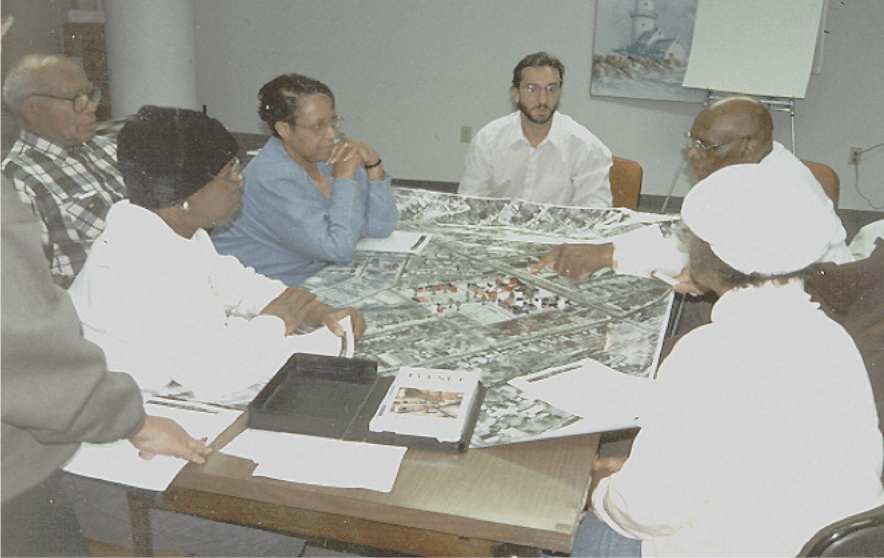

“I spent my first years [as the brownfields coordinator] going to Union Baptist church to tell people about [progress on the Magic Marker site]. The DEP was [at those meetings]. The EPA [too]. Isles was the new non-profit in town.” The Magic Marker site is a notorious property in Trenton that was once active as far back as the 1940s when it was first a battery factory. The site operated as a Magic Marker factory in the 1980s before the owner of the factor, Doral Industries, went bankrupt and vacated the site between 1986 and 1989.

“By the time I [got] here, [this work] was going on maybe 10-15 years. So, the people were probably skeptical, in part because some of those folks were probably told [they] have to live in [these buildings] next to a nasty factory when redlining was going on,” said Capasso.

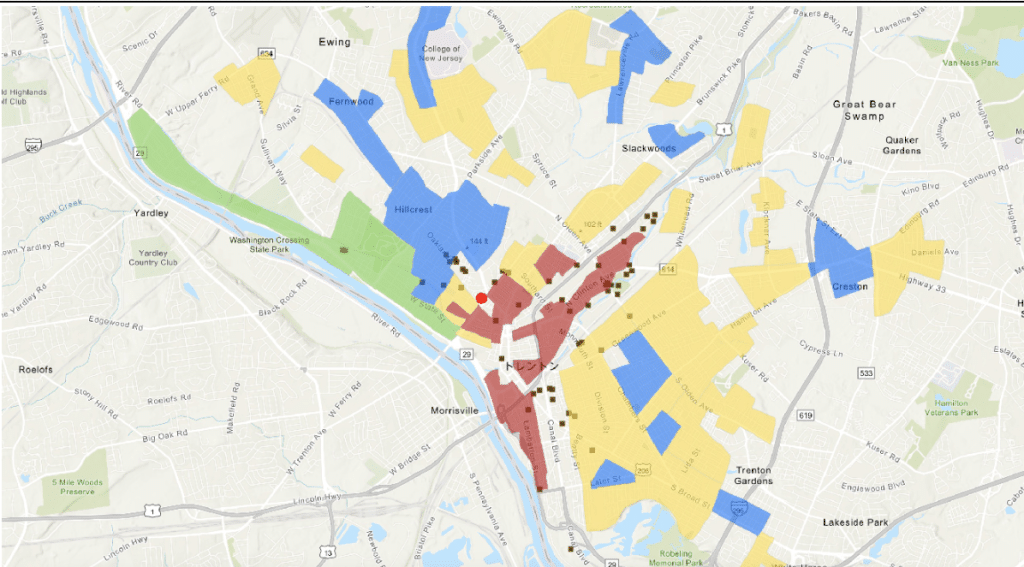

The Department of Environmental Protection has 54 brownfield sites recorded for Trenton in their brownfield dataset. 40 of those sites are located in regions that were designated by the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) as either “declining” (yellow on the map) or “hazardous” (red on the map) in the 1930s.

Documentation from BRS notes that the Magic Marker Site was, “identified early on by the city as a priority, due in large part to the active community group – [the Northwest Community Improvement Association] – that was created to advocate for its redevelopment. As such, it was included within the City’s Homeownership Zone and the Canal Banks Redevelopment Area, and was one of four brownfield sites listed on the City’s initial EPA Pilot Grant workplan in 1995.”

“The folks in the neighborhood [were] mobilized,” Capasso continued. “There’s an important lesson there: if you want to get attention, it doesn’t hurt to get yourself heard and get help.”

Remediating the Magic Marker Site was an expensive endeavor. It cost more than 3.5 million dollars in total. 200,000 dollars came from an EPA clean-up grant, the most the agency awarded at the time.

In June, Trenton received nearly 2 million dollars to clean long-abandoned former New Method Cleaners site; the largest grant amount for brownfields given out by the EPA up to that point. The amount of grant funding has gone up steadily since the brownfield program began in 1995. “The grant [for the New Method Cleaners site project] was 2 million dollars. Before that grants were 1 million [dollars], before that 500,000 [dollars], and before that [200,000] …” said Capasso, “but you can only go for one to two [of those federal] grants at a clip. They end up taking a lot of time. And you know the saying, ‘Free money is never free.’ There’s a lot of regular reporting that needs to be done for these grants.”

This is what makes managing partners like BRS so important for brownfield redevelopment work: they handle a good deal of the logistical work for managing these projects, especially as the number and extent of grant opportunities increases, especially for federal grants.

“In the late-1990s [grant writing] wasn’t done regularly, but now brownfields grants done regularly (every year),” said Capasso. More funding from the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure law opened up more federal granting opportunities. And more and bigger grants means more and bigger remediation projects. “With more funding we have new sites we can look at – more dry cleaners [like New Method] owned by the city,” said Capasso.

Cleaners, like New Method and the countless others, are a priority because of chemicals like perchloroethylene (PCE). PCE is classified by the EPA as a carcinogen, or cancer causing agent.

Exposure to PCE, for example by breathing it in, can also harm the nervous system and negatively impact visual memory, color vision, the ability to process information, headaches, and problems with muscle coordination. Drinking water with elevated levels of PCE can also lead to cancer and kidney damage.

“For all the [brownfields] that the DEP knows about, there’s probably double that. For example, for laundry sites, the DEP has about eight recorded, there’s probably around 200 I found in my inventory…and PCE used in the sites from the 1930s until about 10 years ago is probably still there,” said Capasso.

“[Still] this work is more a real estate thing than a technical thing,” Capasso continued. “For sites in my inventory, they are either city-owned or were owned by the city that private investors are buying…Typically, the city will foreclose sites, [building] a pipeline [for brownfield redevelopment].”

As of the 2018 Brownfields Action Plan put together by the Better Environmental Solutions for Trenton Advisory Committee (currently on hiatus), which guides work for the Trenton Brownfields Program, nearly 200 acres have been remediated.

“If I were to ballpark it, I’d say that there’s another 200 (Acres) to go,” said Capasso. Abandoned lots, which still cover around 10% of the total area of Trenton, state parking lots, and even the highway are all potential brownfields. This problem is exacerbated by the extent of underground storage tanks that contain hazardous waste, which impacts every part of the city.

“Someday we might not have need for a job, but that won’t be for a long time. [It’s essential to Capasso] that we send out these BAP. I want to make sure that we back fill this job.”

“[Capasso has been with the city a long time], but I worry about the continuity of the program when he eventually decides to retire,” Yasenchak confessed.

Though the city has been good about securing external funding sources, internal funding through the city’s Capital budget has been less reliable. “It’s not consistently included in the budget…There are still several large sites that need to be addressed,” Yasenchak revealed. In the case of the Magic Marker project budget, only 275,000 was demarcated in the city’s Capital Budget, which was at the time more than the EPA’s cleanup grant funding.

Maintaining Capasso’s role is essential for setting Trenton apart from every other city in the country and helping to lead the way in brownfield redevelopment.

“A lot of this work is invisible…it could be 5, 10 or even more years, either before the site is clean or at least fixed so it can be redeveloped,” said Capasso, later adding, “I used to show people around the sites before COVID [to get the word out]. I’m just trying to explain things to people. Sometimes, it’s hard to take these technical issues and explain it [to the layperson], but someone has to do it.”