Trenton’s Anti-Bullying Efforts Face Challenges Amid Rising Concerns Over School Safety

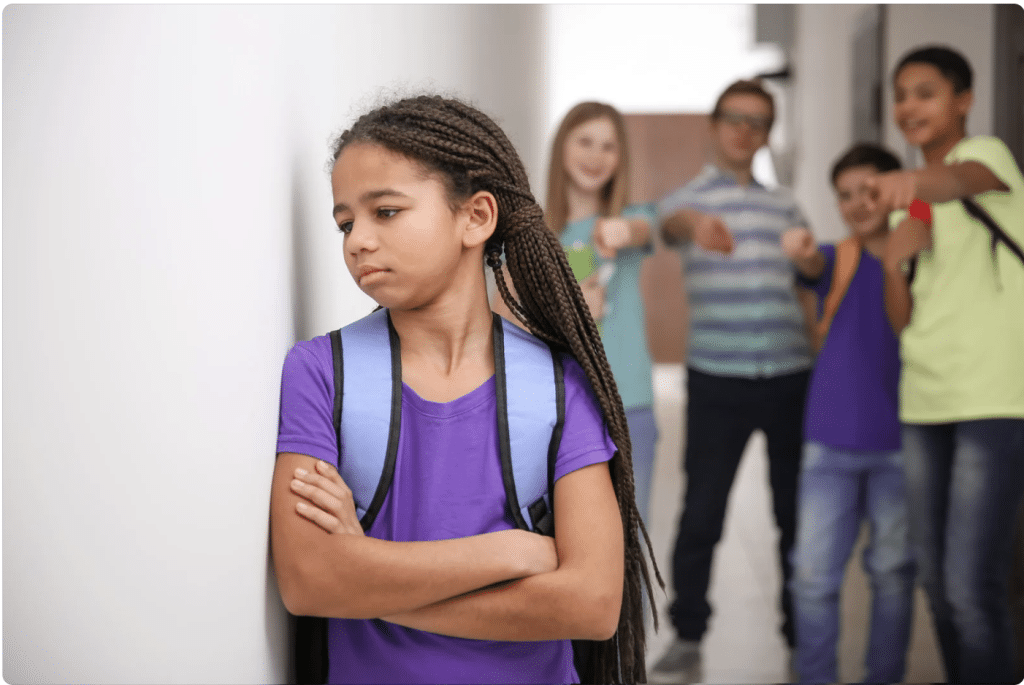

New Jersey may have one of the toughest Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights in the country, but in Trenton, bullying and fighting, particularly at the middle school and high school level, have heightened parental concerns that both schools and parents need to do more to prevent and help students address anti-social behavior.

The 2024 suicide of a 14-year-old teen who attended Trenton’s Ninth Grade Academy, linked to bullying and several other recent instances of fighting and cyberbullying that have escalated into physical violence on or near school grounds, has kept the spotlight on this complex issue.

In response, the Trenton community, civil society, and faith leaders are collaborating with the Trenton schools to give students a voice and a space to discuss school safety and contributing factors to bullying.

One of the most prominent initiatives is the “Focus Group on School and Public Safety,” which gathers 25 community and faith leaders, including current school staff and parents. The Focus Group, which came together in 2021, felt it was time to hear directly from Trenton’s middle and high school students and give them a peer-to-peer platform where they could speak about what can be done to enhance school safety and reduce anti-social behavior.

“We found bullying was too limited a term to encompass the kind of behaviors like fighting and verbal confrontations in the hallways and on school grounds that we are seeing,” says Joyce Kersey, founder and convener of the Focus Group, a retired educator and former two-term Trenton School Board President. “We’re still in the listening stage, but we want to give students a safe space to talk and identify the root causes of the anti-social behavior, whether it is in the classroom, on the way to school, or in the community.”

The group works closely with the Trenton schools’ Culture and Climate department to select 25-30 middle school and high school students, not just model students but those also struggling with academic or behavioral issues, and bring them together in small peer-led round table discussions on school grounds to discuss the issues. The leadership gathers monthly, sharing the students’ feedback with the Trenton School Board and Trenton Superintendent James Earle, and holds a quarterly town hall meeting open to parents and the public.

New Jersey’s Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights

“What parents need to know is that there is a process and they have options,” says Coreen Grooms, an independent education advocate and member of the Focus Group who argues that one of the main obstacles to addressing bullying is that parents don’t know their rights under state law, or that they need to formally report harassment, intimidation or bullying (HIB) to the school or on the Trenton School K-12 page.

The detailed guide for parents, “10 Steps of the Harrassment Intimidation and Bullying (HIB)Complaint and Investigation Process” mandates that school staff report an incident to the principal of the school the same day it is reported to them; that the principal must initiate an investigation of the complaint one school day after the complaint; that the school must inform all suspected victims and offenders of a decision within five days; and, if warranted, make a police report and recommend follow-up counseling for the bully or impose sanctions. Each Trenton school must have an anti-bullying specialist contact, often the guidance counselor, and parents can find that list here for the Trenton schools. The district also provides links to resources for parents on the webpage.

Groom says that if parents feel that the bullying is not being adequately handled by the school, they can go directly to the district level – either the superintendent or the School Board of Education. And if that doesn’t work, they can also file a report with the state or on the New Jersey Department of Education webpage, which has the form in several languages, from Spanish to Creole, at the Division on Civil Rights or, in the case of criminal activity, go directly to the police.

Despite the existence of these resources, community leaders say many Trenton immigrant parents, depending on immigration status, are reluctant to file a Harassment, Intimidation, and Bullying (HIB) form. “A lot of people in our community don’t report with the schools. Even if the form is in Spanish, parents prefer verbal face-to-face contact, or finding an advocate or clergy to go to, because filling out forms is difficult or they just don’t want their name in the system,” according to Reverend Rodriguez, another member of the Focus Group who works closely with the Latino community as Director of Education at Trenton’s Pentecostal Church.

At Wit’s End

Although New Jersey’s Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights (ABR) mandates schools prevent, report, investigate, and respond to harassment, intimidation, and bullying (HIB) incidents within very tight time limits, appointing anti-bullying specialists and safety or “crisis” teams in every school, parents say the Trenton schools are under resourced and that they have difficulty navigating the system and getting rapid responses or follow up to their complaints.

Community leaders also confirm that many Trenton parents report being dismissed when they sought intervention from the schools for safety and bullying issues that affected their children.

“Every parent that has come to me has said that the school defines bullying differently than they do. A lot of times, conflict is not considered bullying, so their concerns are often dismissed unless they can show a clear pattern,” says Rev. Rodriguez.

Even parents who have used the “10 Step Guide” and reporting system say that the Trenton school system has failed to protect their children, whether they are the victims or the aggressors. Some have chosen to remove their children from the Trenton schools altogether, resorting to homeschooling them online. One mother interviewed, Yarissa Roldan, whose daughter was repeatedly bullied for months at the Ninth Grade Academy before being knocked unconscious outside Trenton Central High said her concerns were dismissed and no actions was taken in time to prevent the violence, despite filing multiple reports with the school, including providing video evidence and proof of cyberbullying, to the School Safety team. “I was told that ‘nothing is going to happen’ and that ‘this is just girls’ talk,” Roldan said. Roldan ultimately went to the county and the police, where she pressed charges against the bullies, who were later suspended. She chose to remove her daughter from school.

What does Roldan believe should have happened? Swifter intervention with the parents of the bullies to educate them about sanctions: “I truly believe that the school should have talked to the bullies’ parents earlier when the cyberbullying and the threats started and raised the possibility of charges. That should have happened before my daughter was harmed and had to be removed from the school she attended.”

Roldan also has a 10-year-old son with a learning disability who was bullied by children who she said had behavioral issues. Roldan also removed her son and is schooling him online through the Acellus Academy.

“The district has to do something differently. Nobody wins here –not the victim, nor the aggressor–because the aggressor faces charges,” Roldan said.

Trenton parent advocate and LALDEF (Latin American Legal Defense and Education Fund), Laura Leal, agrees that schools need to do more early intervention to educate parents and children about the long-term consequences of violence and bullying, both for the victims and the aggressors:

“Often in the Latino and other immigrant communities, the parents are afraid to speak to school authorities or the police. But that’s even more reason why the schools need to do more to educate the kids and the parents about the legal consequences and laws against bullying. Not just the Latinx community, but all parents need to know more about the long-term–even lifelong —psychological or criminal legal consequences for their children. They need to know that when you are taken to court as a juvenile for charges, you are fingerprinted and given 10 years of probation, and you have to submit to regular checks at the school.” Leal advocates creating a Trenton bullying hotline.

Overcrowding and understaffing at the high school level

Although parents can tend to place blame on the schools for bullying issues, the root causes of safety in an urban district like Trenton are various and systemic. Groom, Kersey, and other community leaders interviewed suggest that some of the tensions and conflicts may stem from structural pressures at the high school and middle school levels following demographic shifts in Trenton. With an influx of new immigrants in the southern part of the city in recent years, redistricting was necessary, and new attendance zones have concentrated high school-age children at Trenton’s 9th Grade Academy and Trenton Central High, causing overcrowding and understaffing in some cases. To cite just one example, the Ninth Grade Academy, whose enrollment increased by 6% from 2023 to 2024, has a capacity of 500 children but currently serves almost 900, according to Kelly Creque, Special Assistant for Research Evaluation and Assessment for the district.

The redistricting separated adolescents from their “home” neighborhoods and brought children from different wards and ethnic communities together at a vulnerable time in their development. Kersey and others also pointed out that many of the teachers come from outside the Trenton community, which does not help ease tensions because they are perceived as outsiders who need to “learn the kids” as she puts it.

A two-way street: “Parents need to be more involved.”

Trenton school staff on the Focus Group leadership team point to the significant obstacles schools face when anti-bullying specialists do intervene to try to get help for children who are being bullied or who are doing the bullying.

“You can’t just blame the schools because these kids are coming into school with all kinds of past trauma, shame, low self-esteem, and the devastating impact of poverty on families,” said Beverly Smith, an elementary school counselor and Crisis Response Team coordinator for the district.

As a counselor, Smith speaks from experience, adding, “It’s got to be a two-way street. Parents need to be more involved. A lot of times, even when we do intervene with parents whose children are being bullied or who are doing the bullying, it’s difficult to get them on board. They don’t want mental health professionals involved. There’s the stigma. Some see it as shameful,” Smith adds, “Often a lot of children doing the bullying have been bullied themselves. Schools can’t force parents to get help for their kids. If parents don’t want to seek help, or unless it’s court-ordered, there’s often nothing we can do.”

What could schools be doing better? Smith says, “We need more intensive trauma-informed training of staff who are on the front lines with the kids. Not just with security and school safety teams at the high school and middle school, but starting with the secretaries, and all the staff on up, including janitorial services. These are the people who interact and know the kids intimately, their family situations, and can help investigate and ease situations.”

But Smith points out that bullying is not a new problem and Trenton schools have not received enough credit for their strong focus in recent years on teaching restorative practices, like conflict resolution, and Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) skills throughout the schools, which cultivate student self-esteem and are aimed at reducing anti-social behavior. One notable initiative is “The Leader in Me” program, an evidence-based PK-12 model that fosters leadership and life skills in students and aims to boost academic achievement, while also addressing social and emotional learning (SEL) needs. The “Leader in Me” teaches students how to manage their emotions and be clear about their intentions and boundaries, skills that help them stand up to bullying.

But schools cannot single handedly solve Trenton’s bullying problems. Educators like Smith and Kersey say that community leaders must also step up to the task of educating parents and children about mental health issues and how to respond to bullying and resolve conflicts on and offline.

Reverend Rodriguez agrees: “The Trenton schools are doing the best they can with the resources and the manpower they have. But they can only do so much. It takes a village and it has to be a partnership with parents and the community.”

Rodriguez himself is leading the way with Trenton’s Jericho Project, a faith-based anti-bullying and suicide prevention campaign that reaches between 100-150 middle and high school students, while providing parents with resources to identify signs of bullying and suicidal ideation. The Jericho Project offers “Plugged In” groups that give students a safe space to talk to peers, youth mentors, and speakers who discuss mental health and help them practice conflict resolution strategies and skills to stand up to bullying. Rodiguez, who has plans to “adopt” individual Trenton schools to work with the Jericho Project, says he takes a “proactive approach”: “The Jericho Project is trying to break the stigma around mental health, that ‘my child is crazy’ or ‘unstable. He’s a child, and they are trying to find their identity. We also want to empower the kids so they can feel less isolated and ashamed when they are bullied and learn to be good bystanders or ‘upstanders’ when they witness bullying.”

See the New Jersey Schools comprehensive guide on how to talk to kids about these issues.