Architecture as Evidence for Reparative Futures

A Reparative Policy Argument for ADOS Justice through the Built Environment

When we walk through our cities, the buildings, streets, and landscapes tell stories. Some of those stories are of opportunity and pride, but for American Descendants of Slavery. (ADOS), the built environment often tells another story: one of exclusion, displacement, and

loss.

Architecture is not neutral. The housing projects of the mid-20th century, the redlined neighborhoods of the 1930s, and the highways that cut through thriving Black business districts are not accidents — they are evidence. They stand as physical testimony of a

planning system that codified inequality into brick, steel, and concrete. What is missing — entire erased neighborhoods, demolished churches, or vacant lots where families once built wealth — is also evidence. The absence itself tells us what was taken.

As I write this, I am reminded of our own architectural lineage in Trenton — the Carver Y located at 40 Fowler Street, the historic Higbee School on Bellevue Avenue, and the former Lincoln School, now Rivera-Muñoz. Trenton, the capital city of New Jersey, holds a rich, layered Black history that is dangerously close to erasure — not through accident, but through neglect, ignorance, and redevelopment practices that sever memory instead of honoring it.

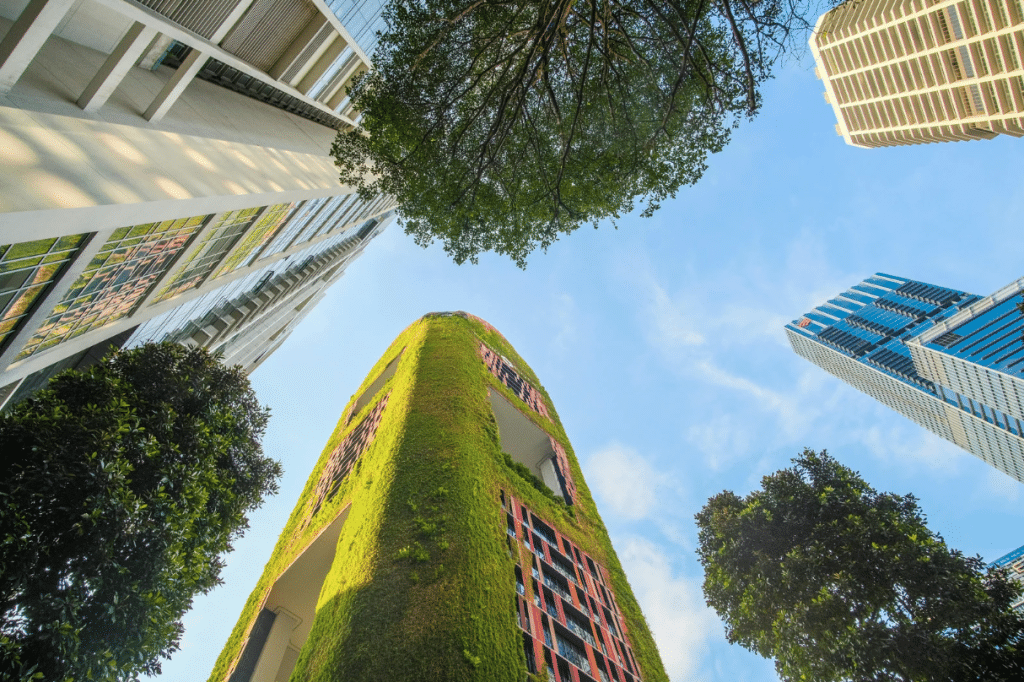

But if architecture can bear witness to harm, it can also serve as a pathway to repair. Imagine housing policies that prioritize wealth-building for ADOS families — not just “affordable” rentals. Imagine new development that requires cultural spaces to honor erased histories. Imagine land trusts and cooperative housing owned and governed by ADOS-led organizations, ensuring that communities cannot be displaced again.

This is what I call architecture as evidence for reparative futures. It is about more than design — it is about justice. Architecture must move from being a record of inequity to becoming proof of repair. That requires intentional policies: prioritizing public land for ADOS ownership, mandating reparative benefits within redevelopment, dedicating funding streams to. trauma-informed design, and building archives that document dispossessed neighborhoods as formal evidence supporting reparations claims.

Urban planning sets the framework — but architecture makes it visible. If policymakers commit to reparative approaches, our built environment can testify not only to where we have failed, but to how we chose to heal. The built environment will always tell a story. The question before us is whether it will continue to testify to exclusion — or stand as evidence of equity restored.

—

Stephani Register is an Urban Planner, community advocate, and Founder of Recovery is Essential (RIE), working at the intersection of recovery, land justice, and Black reparative policy.